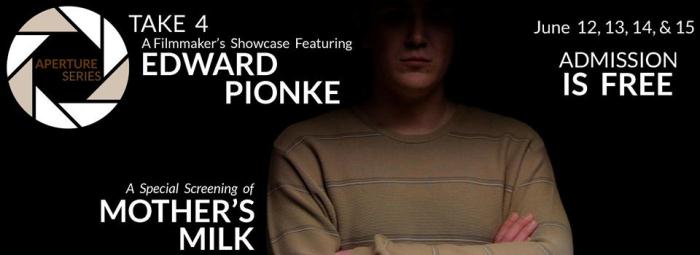

Aperture – Take 4

Oracle Film presents…

Aperture Series

Take 4 – Edward Pionke

Screening: MOTHER’S MILK

Reserve Your Seats NowAdmission is FREE in Public Access Theatre

June 12, 13, and 14 at 8:00 pm

June 15 at 7:00 pm

Oracle Film is excited to showcase the work of award winning Chicago Filmmaker, Edward Pionke. Join us for an evening for Mr. Pionke’s film, MOTHER’S MILK, and then stick around for a talkback and reception with the filmmaker.

[ERROR: No URL or video ID was passed to the Vimeo BBCode]SYNOPSIS of MOTHER’S MILK

Claude is a university statistics professor with a dark side. Kim is the young woman he kidnaps to satisfy his dysfunctional needs. In this psychological thriller, tenderness develops between a psychopath and his captive. The simmering plot boils over as they move inexorably to a climax that will forever change each of their lives.

Intended for Mature Audiences

AWARDS for MOTHER’S MILK:

Best Director – International Film Awards Berlin

Best Screenplay – NW Ohio Independent Film Festival

Best Actor – International Film Awards Berlin

Best Actress – NW Ohio Independent Film Festival

ABOUT APERTURE SERIES at Oracle

Oracle Film presents the APERTURE SERIES so Chicago can meet amazing filmmakers. Each series consists of a weekend dedicated to showcasing the films of independent filmmakers, providing them with an audience while offering free screenings and Q&A sessions to the community in Oracle’s Public Access Theatre.

ABOUT THE FILMMAKER: Edward Pionke

Ed Pionke is a Chicago area native living in Chicago’s Margate Park neighborhood for the past 20 years.He studied engineering and mathematics at the University of Illinois, is an Associate of the Society of Actuaries and a lawyer. He worked in the pension and employee benefits field as an actuary and lawyer for over 20 years. Ed began writing screenplays in 2009. Mother’s Milk is his first film which he wrote,produced and directed. He is currently involved in post-production on Residuum, his second film, which is expected to be completed in 2014. He is also hoping to begin production on Asymptotes, his latest screenplay, sometime in 2014.

DIRECTOR’S STATEMENT from Edward Pionke

What is my “philosophy” on film? This is a difficult question in two major respects. First, developing a coherent aesthetic is an ongoing process so that my views on what comprises the essential components of a good film are in flux and what I think at one given point in time is subject to change. Second, because film is so experiential, the filmmaker’s philosophy or manifesto, is, or should be, largely irrelevant. A film should stand on its own without the need for explanation. That said, the second point above may shed some insight into my personal opinion on what I consider a good film. Being experiential in nature, a good film should be felt on an emotional level and not so much understood on a rational or intellectual level. Just this criterion immediately differentiates between most films made and the few good ones that rise to another level and are considered masterpieces of the medium.

The question that seems to pervade many filmmakers work is whether the audience will get it. The question that should be asked is whether the audience will feel it. This difference immediately reveals itself in the content of the film and the way it is presented. On the one hand, one director will be interested only in presenting what would actually take place in the scene. His emphasis is on truth to the story and performances that are consistent with that truth. On the other hand, another director will be preoccupied with the delivery of information, regardless of whether what the actors do and say is consistent with what would actually be done and said in the scene in a “real” world. To attach more words to the difference, on the one hand we have a director who is concerned with keeping the film at all times organic while on the other hand we have a director who is willing to introduce plastic elements into the film which serve merely to provide information.

As an example, consider a scene of a married man sitting at a bar who is approached by an attractive single woman, who happens to be an alcoholic, who begins to flirt with him. It is not uncommon to see such a scene filled with elements that serve no purpose but to provide the viewer information. For example we may see the camera zoom in on his hand as he takes a drink to observe that he has a wedding ring. We may be privy to a short private conversation between the woman and the bartender who remarks “rough night last night, huh”? We may see the man take out his wallet and show the

woman pictures of his kids. The director wants us to know that the man is married, he has children and the woman might have a problem with alcohol. No matter that the bartender, knowing the woman’s proclivities, would never ask that question because the scene had been played out so many times before, no matter that the man would never show pictures of his kids because he finds the woman attractive and is subconsciously burying his family life, no matter that we have to endure a zoom shot on a wedding ring possibly taking us out of the mood of the scene. I call these things “pointers” because the director is feeling the need to point things out to us. Of course the score can also be employed as yet another pointer, usually one to tell us how to feel because the director fears the scene itself is not sufficient in that respect. And of course the close up of the ring won’t be enough, at some point we will need to get very close to the actors faces especially as some revealing line of dialogue is delivered.

The above is in contrast to the scene shot by a director who only asks the question what would the characters actually do and say in this particular circumstance and who is content to rely on that reality to carry us through the scene and into the next. No pointers are necessary. Not a lot of cuts, certainly no zoom onto a wedding ring, maybe just one long take with a static camera and no score whatsoever. This is bold story telling because the director must be confident that the story stands on its own two feet even though the viewer may at times be somewhat disoriented with the lack of information. The miracle of these films is that the viewer never does feel disoriented because of the truth of the emotional content of the film. It is enough to feel it is real, we do not need to know or be convinced it is real.

As further examples of the above dichotomy one can compare Bresson’s film “A Man Escapes” to “The Shawshank Redemption” or Bresson’s “Joan of Arc” to other films of the same title or Tarkovsky’s “Stalker” to Ridley Scott’s “Prometheus”.* Taking Joan of Arc as an example, Bresson realized that the story of a person who first recants her faith in the face of death and then, tortured by having made that decision, reaffirms her faith knowing she will burn at the stake is such a powerful story that it needs no embellishment. A good performance by the actors will do. The set is minimalist; the action, if you can call it that, subdued; and the shooting simple and non-intrusive. No need to show a mannish Joan in full body armor leading an army to victory. No sword fights, casts of thousands, blood and guts necessary. His film is so powerful because he let the story and performance speak for themselves.

Contained within this organic method of storytelling is something about the director’s attitude towards his audience. Many of these directors have said that they make films primarily for themselves. At first blush this may seem egocentric but in fact it is exactly the opposite. The director who feels that if he makes a film that he himself would like to see then others will like it also, implicitly trusts his audience and does not place himself above them. The director who is using pointers to make sure he is understood implicitly places himself above his audience. This type of director often seems pedantic and at other times too eager to show others his cleverness. Cleverness is anathema to art. Honesty is not.

And yet another characteristic of such story telling is the director’s attitude towards his subject matter. He does not try to wrap things up in a bow. It is okay if things are a bit ambiguous, it is okay if things are not settled, it is okay that there is more gray than black and white. This, to me, is reflective of life itself. If a film is seeking to give an answer, I often feel it suffers either from obviousness (because the question is so simple) or from hubris (because the question is profound but unanswerable). What is left? Merely a sharing of an experience which the director finds emotionally moving and hopes his audience will too.

In a plastic film filled with pointers and the prestidigitation filmmakers so often employed, I feel the end result is like a connect-the-dots sketch. The outline is perfectly clear, but there is no substance to the picture – it is flat and emotionally empty. In an organic film told simply and truthfully, the outline may be blurred, different people may see entirely different things, but seen at a certain angle and from a certain distance it is moving and there is some undeniable truth to it that transcends the particularity of the story. This is because only absolute truth in the particularity can possibly lead to any sort of larger truth.

Too many films seem to have been concocted by working backwards along these lines. The director has some overarching theme that he must present at all costs and he forces his story into that framework not realizing that by doing so he distorts its reality and makes it impossible for it to even stand alone as truthful let alone transcend into something more universal. It is somewhat paradoxical then that a film based on a story told simply, truthfully, without embellishment of any kind can rise to the heights of great art while other films using all the tools at the craftsman’s disposal, no matter how expertly employed, fall short of the mark. In the end it is often simply a result of content and the story that was there to be told in the first place. It is unfortunate that too many directors just don’t have much to say. They fall back on “production value”, that most invidious phrase, and cleverness and eye candy and shock value to make something that tricks the viewer into thinking they have seen something worthwhile. That thought fades, however, as do those films, into irrelevance.

Although there is much more I can say about what I think makes a good film, it is perhaps best just to end here and reflect on what all this means to my own films. It is aspirational. And that is a third reason why it is difficult for me to put forth a manifesto. It is impossible for me to live up to it. My tenets are drawn from the Bergman’s, Tarkovsky’s and Bresson’s of the world and, while I feel the truth of their lessons, to follow them is a far more difficult task. It is a truism that, given today’s technology, it is relatively easy to make a film. It remains, however, incredibly difficult to make a good one. That said, I count myself among the filmmakers who will continue to try with the knowledge that though an individual film be stillborn, the act of conceiving it is so enjoyable that it is difficult not to hop in the sack once again.

*Not to denigrate all of Scott’s work as ALIEN and BLADERUNNER are fine films.